![]() Chapter

13: The

Behavior of a Saintly Person

Chapter

13: The

Behavior of a Saintly Person

(1) S'rî Nârada said: 'Someone capable

of what I described before, should wander around from place to place

without any form of material attachment and ultimately with nothing but

his body not stay in any village longer than a single night [see

also the story of King Rishabha 5.5:

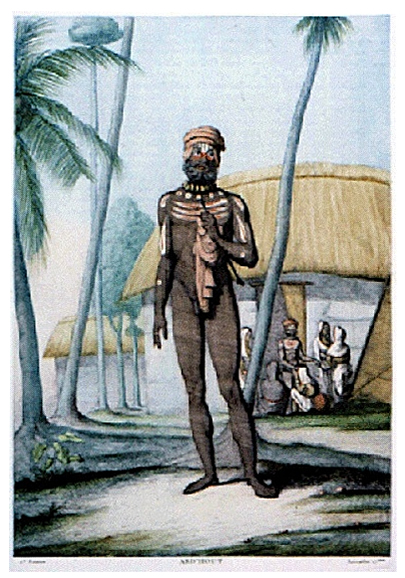

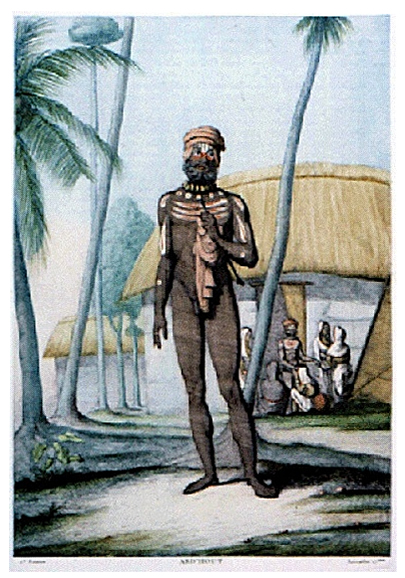

28]. (2) If

the renunciate [sannyâsî]

wears clothing at all, it should be nothing but some covering for his

private parts. Except in case of distress, he should not take to

matters he has given up; he normally carries nothing but the

marks of his renunciation: his rod [danda] and such. (3) With

Nârâyana as

his refuge living on alms only he, satisfied within, all alone and not

depending on anyone or anything, moves

around in perfect peace as a well-wisher to all living beings. (4) He

should

see

this universe of cause and effect as existing within the

everlasting Self in the beyond and see the Supreme Absolute itself as

pervading the world of cause and effect everywhere [compare B.G. 9: 4]. (5) The

soul moves from waking to sleeping to

intermediate dreaming [see also 6.16: 53-54]. Because

of

that someone [like him] in

regard of the Soul considers the

states of being bound, of being conditioned and being liberated as in fact nothing

but

illusory. (6) He

should not rejoice in the death of

the body that is certain, nor in the life of the body that is

uncertain, instead he should observe the supreme [command] of Time

that

rules

the

manifestation

and

disappearance

of

all

living

beings. (7) He should not be

fixed on time bound literatures, nor depend on a career. Accusations

and pedantry should be given up, nor should he side with group bound

conjecture, opinion and speculation [politics]. (8) He

should not seek followers, nor should he engage in diverse

literary exercises or read such writings. He should not subsist on

lecturing nor set up an enterprise [for building temples e.g.]. (9) A

peaceful and equal

minded renunciate does not always

have to adopt the symbols of

his

spiritual position [the danda etc. of his âs'rama *], he

as a great soul may just as well

abandon them. (10) Even

though he externally may not directly be

recognized as a renunciate, his purpose is clear. Such a saintly person

may feel the need to present himself in society like an excited boy or,

e.g. once having been a great orator, now present himself as a man of

little eloquence.

(11) As an example of such a hidden identity one [often] recites a very old story about a conversation between Prahlâda and a saintly man who lived like a python. (12-13) Prahlâda, the favorite of the Supreme Lord, once met such a saint when he with a few royal associates was traveling around the world in an effort to understand the motives of the people. At the bank of the Kâverî river on a slope of the mountain Sahya, he witnessed the purity and profundity of the spiritual radiance of the man who was laying on the ground with his entire body covered with dirt and dust. (14) From what he did, how he looked, from what he said as also by his age, occupation and other marks of identity the people could not decide whether or not that man was someone they knew. (15) After paying his respects and honoring him by, according to the rules, touching his lotus feet with his head, the great Asura devotee of the Lord, eager to know him, asked the following question. (16-17) 'I see you are maintaining quite a fat body like you are someone lusting after the money. People who always worry about an income are surely of sense gratification. Wealthy people, they who enjoy this world and think of nothing else, therefore become [easily] as fat as this body of yours. (18) It is clear that you lying down doing nothing oh man of the spirit, can have no money for enjoying your senses. How can, without you enjoying your senses, your body be this fat oh learned one? Excuse me for asking you, but can you please tell us that? (19) Despite of your being so learned, skilled and intelligent and your talent to speak nicely and your inner balance, you lie down observing how the people are engaged in productive labor!'

(20) S'rî Nârada said: 'The great saint thus being questioned by the Daitya king smiled at him and was, captivated by the beauty and love of his words, willing to reply. (21) The brahmin said: 'Oh best of the Asuras, you who are appreciated by all civilized men, know from your transcendental vision all about the matters people during their lifetime are inclined to and turn away from. (22) With Nârâyana deva our Lord always in one's heart, someone by his devotion alone will shake off all ignorance, the way darkness is dispelled by the sun. (23) Nevertheless I will try to answer all your questions according to what I've heard [from the sages and their scriptures] oh King, for you are worthy to be addressed by someone who desires the purification of his heart. (24) Under the influence of worldly interests, I have been catering to my lusty appetites. I have, because of these material desires, been impelled to actions that were unfulfilling and was thus tied to different types of birth. (25) I

unexpectedly

acquired this [human]

position again, after because of my karma having wandered from the

heavenly gate of liberation to lower species of

life [see also B.G. 8:

16 and **]. (26) But

seeing

how

one

in

that

position

acting

for

the

sake of the pleasure of men and women and the avoidance

of misery, achieves opposite results, I have now ceased with that kind

of engagements. (27) Now

that

I

in

my

contemplation

of

these

matters

have

witnessed the extend to which the spirit of intimate

human contact assumes the form of sensual pleasure [or, the degree to

which the demands of this world are associated with sense

gratification], I have entered this silence. Happiness is the natural

state

of the living entity and therefore I have definitively put an end to

all of this. (28) Someone situated in this

world is by the false attraction

of that material place entangled in dreadful material

affairs that are strange to him. Because of that estrangement he

forgets about the interest of his heart and soul. (29) The same way as a thirsty human being who fails to notice water that is overgrown

by grass then ignorantly looks

for it elsewhere, also someone

looking for money [and other material benefits] runs after a

mirage [of happiness]. (30) Someone who with his body and

everything belonging to it, is subjected to the superior control [of

the material world], searches for

the happiness of the soul by trying to diminish his misery. But he,

helpless without the Supreme Lord, is time and again disappointed in

his plans

and

actions. (31) [And

if he once happens to succeed,] of

what use is the incidental success of fighting adverse consequences to a mortal person who

is not free from the threefold miseries as created by himself, by

others

and by nature? Where do such successes lead to? What is their value? (32) I

see the miseries of

the greedy rich and wealthy; as a victim of their senses they in their

fear have sleepless nights in

which they see danger coming from all sides. (33) He who lives for the money is always afraid

of the government, of thieves,

of enemies, relatives, animals and birds, of beggars, of Time and of

himself. (34) Someone

of

intelligence

has

to

give

up

that what is the original cause

leading to all the lamentation,

illusion, fear, anger, attachment, poverty, toiling and so on of the

human being: the desire for power and wealth [***].

(25) I

unexpectedly

acquired this [human]

position again, after because of my karma having wandered from the

heavenly gate of liberation to lower species of

life [see also B.G. 8:

16 and **]. (26) But

seeing

how

one

in

that

position

acting

for

the

sake of the pleasure of men and women and the avoidance

of misery, achieves opposite results, I have now ceased with that kind

of engagements. (27) Now

that

I

in

my

contemplation

of

these

matters

have

witnessed the extend to which the spirit of intimate

human contact assumes the form of sensual pleasure [or, the degree to

which the demands of this world are associated with sense

gratification], I have entered this silence. Happiness is the natural

state

of the living entity and therefore I have definitively put an end to

all of this. (28) Someone situated in this

world is by the false attraction

of that material place entangled in dreadful material

affairs that are strange to him. Because of that estrangement he

forgets about the interest of his heart and soul. (29) The same way as a thirsty human being who fails to notice water that is overgrown

by grass then ignorantly looks

for it elsewhere, also someone

looking for money [and other material benefits] runs after a

mirage [of happiness]. (30) Someone who with his body and

everything belonging to it, is subjected to the superior control [of

the material world], searches for

the happiness of the soul by trying to diminish his misery. But he,

helpless without the Supreme Lord, is time and again disappointed in

his plans

and

actions. (31) [And

if he once happens to succeed,] of

what use is the incidental success of fighting adverse consequences to a mortal person who

is not free from the threefold miseries as created by himself, by

others

and by nature? Where do such successes lead to? What is their value? (32) I

see the miseries of

the greedy rich and wealthy; as a victim of their senses they in their

fear have sleepless nights in

which they see danger coming from all sides. (33) He who lives for the money is always afraid

of the government, of thieves,

of enemies, relatives, animals and birds, of beggars, of Time and of

himself. (34) Someone

of

intelligence

has

to

give

up

that what is the original cause

leading to all the lamentation,

illusion, fear, anger, attachment, poverty, toiling and so on of the

human being: the desire for power and wealth [***].

(35) The working bees and the big snakes in this world are in this matter our first-class gurus: from what they teach we find the satisfaction [of being happy as one is] and the renunciation [of not seeking things elsewhere]. (36) Someone comes to take the money that was as difficult to acquire as the honey and eventually kills the owner in the process; thus I learned from the honeybee to detach from all desires. (37) Being disinclined the soul is happy with that what was obtained without endeavoring. Finding nothing, I just lie down for many days and exist like a python. (38) Sometimes I eat little, sometimes I eat a lot of food that sometimes is fresh and sometimes is stale or this time is palatable and that time is tasteless. Sometimes food is brought to me with respect and sometimes it is offered in disrespect. Thus I eat during the night or else during the day whenever it is available. (39) With a happy mind I am clothed in what destiny offers me, be it linen, silk or cotton, deerskin, a loincloth, bark or whatever material. (40) Sometimes I lay down on the earth, on grass, on leaves, on stone or on a pile of ash and sometimes, when someone wishes me to, I lay down in a palace on a first-class bed with pillows [see also B.G. 18: 61]. (41) Sometimes I bathe nicely, smear my body with sandalwood paste, properly dress, wear garlands and various ornaments and sit on a chariot, an elephant or the back of a horse. And sometimes I wander around completely naked as if haunted by a ghost oh mighty one. (42) I do not curse the people but do not praise the people either who have different natures. I pray for the ultimate benefit of all that is found in the Oneness of the Greater Soul. (43) The sense of discrimination should be offered as an oblation in the fire of consciousness, consciousness should be offered in the fire of the mind and the mind that is the root of all confusion must be offered in the fire of the false self. That variable ego should, following this principle, be offered in the complete of the material energy. (44) A mindful person who sees the truth should for the sake of his self-realization offer the complete of his material energy as an oblation. When he because of that offering has lost his interest [in the world], he thus has understood his essence and retires. (45) This story about myself I now submit to you like this in utter confidence. But it might be so that you from your good self, as a man of transcendence with the Supreme Lord, find it contrary to the customary scriptural explanation.'

(46) S'rî Nârada said: 'Thus having heard from the holy man about the dharma of the paramahamsas [see also 6.3: 20-21], the Asura lord most pleased, after duly honoring him took leave and returned home.'

(11) As an example of such a hidden identity one [often] recites a very old story about a conversation between Prahlâda and a saintly man who lived like a python. (12-13) Prahlâda, the favorite of the Supreme Lord, once met such a saint when he with a few royal associates was traveling around the world in an effort to understand the motives of the people. At the bank of the Kâverî river on a slope of the mountain Sahya, he witnessed the purity and profundity of the spiritual radiance of the man who was laying on the ground with his entire body covered with dirt and dust. (14) From what he did, how he looked, from what he said as also by his age, occupation and other marks of identity the people could not decide whether or not that man was someone they knew. (15) After paying his respects and honoring him by, according to the rules, touching his lotus feet with his head, the great Asura devotee of the Lord, eager to know him, asked the following question. (16-17) 'I see you are maintaining quite a fat body like you are someone lusting after the money. People who always worry about an income are surely of sense gratification. Wealthy people, they who enjoy this world and think of nothing else, therefore become [easily] as fat as this body of yours. (18) It is clear that you lying down doing nothing oh man of the spirit, can have no money for enjoying your senses. How can, without you enjoying your senses, your body be this fat oh learned one? Excuse me for asking you, but can you please tell us that? (19) Despite of your being so learned, skilled and intelligent and your talent to speak nicely and your inner balance, you lie down observing how the people are engaged in productive labor!'

(20) S'rî Nârada said: 'The great saint thus being questioned by the Daitya king smiled at him and was, captivated by the beauty and love of his words, willing to reply. (21) The brahmin said: 'Oh best of the Asuras, you who are appreciated by all civilized men, know from your transcendental vision all about the matters people during their lifetime are inclined to and turn away from. (22) With Nârâyana deva our Lord always in one's heart, someone by his devotion alone will shake off all ignorance, the way darkness is dispelled by the sun. (23) Nevertheless I will try to answer all your questions according to what I've heard [from the sages and their scriptures] oh King, for you are worthy to be addressed by someone who desires the purification of his heart. (24) Under the influence of worldly interests, I have been catering to my lusty appetites. I have, because of these material desires, been impelled to actions that were unfulfilling and was thus tied to different types of birth.

(25) I

unexpectedly

acquired this [human]

position again, after because of my karma having wandered from the

heavenly gate of liberation to lower species of

life [see also B.G. 8:

16 and **]. (26) But

seeing

how

one

in

that

position

acting

for

the

sake of the pleasure of men and women and the avoidance

of misery, achieves opposite results, I have now ceased with that kind

of engagements. (27) Now

that

I

in

my

contemplation

of

these

matters

have

witnessed the extend to which the spirit of intimate

human contact assumes the form of sensual pleasure [or, the degree to

which the demands of this world are associated with sense

gratification], I have entered this silence. Happiness is the natural

state

of the living entity and therefore I have definitively put an end to

all of this. (28) Someone situated in this

world is by the false attraction

of that material place entangled in dreadful material

affairs that are strange to him. Because of that estrangement he

forgets about the interest of his heart and soul. (29) The same way as a thirsty human being who fails to notice water that is overgrown

by grass then ignorantly looks

for it elsewhere, also someone

looking for money [and other material benefits] runs after a

mirage [of happiness]. (30) Someone who with his body and

everything belonging to it, is subjected to the superior control [of

the material world], searches for

the happiness of the soul by trying to diminish his misery. But he,

helpless without the Supreme Lord, is time and again disappointed in

his plans

and

actions. (31) [And

if he once happens to succeed,] of

what use is the incidental success of fighting adverse consequences to a mortal person who

is not free from the threefold miseries as created by himself, by

others

and by nature? Where do such successes lead to? What is their value? (32) I

see the miseries of

the greedy rich and wealthy; as a victim of their senses they in their

fear have sleepless nights in

which they see danger coming from all sides. (33) He who lives for the money is always afraid

of the government, of thieves,

of enemies, relatives, animals and birds, of beggars, of Time and of

himself. (34) Someone

of

intelligence

has

to

give

up

that what is the original cause

leading to all the lamentation,

illusion, fear, anger, attachment, poverty, toiling and so on of the

human being: the desire for power and wealth [***].

(25) I

unexpectedly

acquired this [human]

position again, after because of my karma having wandered from the

heavenly gate of liberation to lower species of

life [see also B.G. 8:

16 and **]. (26) But

seeing

how

one

in

that

position

acting

for

the

sake of the pleasure of men and women and the avoidance

of misery, achieves opposite results, I have now ceased with that kind

of engagements. (27) Now

that

I

in

my

contemplation

of

these

matters

have

witnessed the extend to which the spirit of intimate

human contact assumes the form of sensual pleasure [or, the degree to

which the demands of this world are associated with sense

gratification], I have entered this silence. Happiness is the natural

state

of the living entity and therefore I have definitively put an end to

all of this. (28) Someone situated in this

world is by the false attraction

of that material place entangled in dreadful material

affairs that are strange to him. Because of that estrangement he

forgets about the interest of his heart and soul. (29) The same way as a thirsty human being who fails to notice water that is overgrown

by grass then ignorantly looks

for it elsewhere, also someone

looking for money [and other material benefits] runs after a

mirage [of happiness]. (30) Someone who with his body and

everything belonging to it, is subjected to the superior control [of

the material world], searches for

the happiness of the soul by trying to diminish his misery. But he,

helpless without the Supreme Lord, is time and again disappointed in

his plans

and

actions. (31) [And

if he once happens to succeed,] of

what use is the incidental success of fighting adverse consequences to a mortal person who

is not free from the threefold miseries as created by himself, by

others

and by nature? Where do such successes lead to? What is their value? (32) I

see the miseries of

the greedy rich and wealthy; as a victim of their senses they in their

fear have sleepless nights in

which they see danger coming from all sides. (33) He who lives for the money is always afraid

of the government, of thieves,

of enemies, relatives, animals and birds, of beggars, of Time and of

himself. (34) Someone

of

intelligence

has

to

give

up

that what is the original cause

leading to all the lamentation,

illusion, fear, anger, attachment, poverty, toiling and so on of the

human being: the desire for power and wealth [***]. (35) The working bees and the big snakes in this world are in this matter our first-class gurus: from what they teach we find the satisfaction [of being happy as one is] and the renunciation [of not seeking things elsewhere]. (36) Someone comes to take the money that was as difficult to acquire as the honey and eventually kills the owner in the process; thus I learned from the honeybee to detach from all desires. (37) Being disinclined the soul is happy with that what was obtained without endeavoring. Finding nothing, I just lie down for many days and exist like a python. (38) Sometimes I eat little, sometimes I eat a lot of food that sometimes is fresh and sometimes is stale or this time is palatable and that time is tasteless. Sometimes food is brought to me with respect and sometimes it is offered in disrespect. Thus I eat during the night or else during the day whenever it is available. (39) With a happy mind I am clothed in what destiny offers me, be it linen, silk or cotton, deerskin, a loincloth, bark or whatever material. (40) Sometimes I lay down on the earth, on grass, on leaves, on stone or on a pile of ash and sometimes, when someone wishes me to, I lay down in a palace on a first-class bed with pillows [see also B.G. 18: 61]. (41) Sometimes I bathe nicely, smear my body with sandalwood paste, properly dress, wear garlands and various ornaments and sit on a chariot, an elephant or the back of a horse. And sometimes I wander around completely naked as if haunted by a ghost oh mighty one. (42) I do not curse the people but do not praise the people either who have different natures. I pray for the ultimate benefit of all that is found in the Oneness of the Greater Soul. (43) The sense of discrimination should be offered as an oblation in the fire of consciousness, consciousness should be offered in the fire of the mind and the mind that is the root of all confusion must be offered in the fire of the false self. That variable ego should, following this principle, be offered in the complete of the material energy. (44) A mindful person who sees the truth should for the sake of his self-realization offer the complete of his material energy as an oblation. When he because of that offering has lost his interest [in the world], he thus has understood his essence and retires. (45) This story about myself I now submit to you like this in utter confidence. But it might be so that you from your good self, as a man of transcendence with the Supreme Lord, find it contrary to the customary scriptural explanation.'

(46) S'rî Nârada said: 'Thus having heard from the holy man about the dharma of the paramahamsas [see also 6.3: 20-21], the Asura lord most pleased, after duly honoring him took leave and returned home.'