![]() Chapter 8: The

Rebirth

of

Bharata

Mahârâja

Chapter 8: The

Rebirth

of

Bharata

Mahârâja

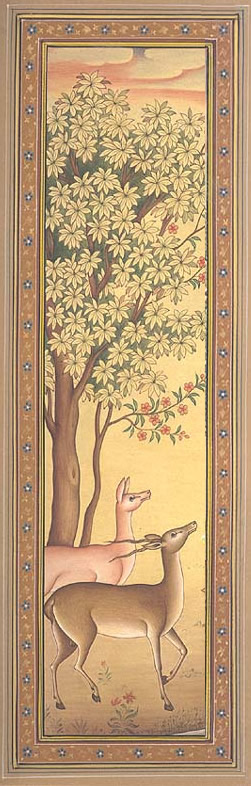

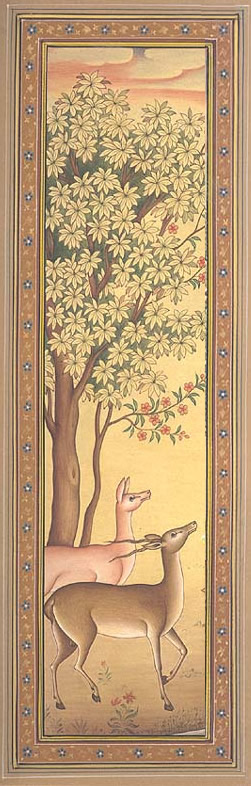

(1) S'rî S'uka said: 'Once upon a time having

taken a bath in the great Gandakî he [Bharata] after

performing his daily duties sat

for a few minutes down on the bank of the river to chant the transcendental syllable [AUM]. (2) Oh King, he then saw a

single

doe which being thirsty had come to the river. (3) At the moment

it eagerly drank from the water,

nearby the loud roar of a lion sounded that terrifies all living

beings. (4) When

the doe heard that

tumultuous

sound she fearfully looking about, immediately without having quenched

her thirst out of fear for the lion leaped over the river. (5) Because

of

the

force

of

that

leap

in

great

fear

she

being

pregnant

lost

her baby which having slipped from

her womb fell into the water. (6) Exhausted

from

the miscarriage caused by the jumping and the fear, the black doe

being separated from the flock fell somewhere down into a

cave and died. (7) Seeing how that deer calf being separated

from its kind, helplessly floated away in the stream, the wise king

Bharata considering it orphaned, took it as a friend compassionately to

his âs'rama. (8) Adopting

it

as

his

own

child,

feeding

it

every

day,

protecting

it,

raising

it and petting it, he got greatly

attached to this deer calf. Within a couple of days he thus, having

given up his routines, his self-restraint and his worship

of

the Original Person, lost his entire practice of detachment. (9)

'Alas! [he thought to himself], by the Controller turning the wheel of

time this creature was deprived of its family, friends and relatives.

Finding me for its shelter, it has only me as its father, mother,

brother and member of the herd. Surely having no one else it puts

great faith in me as the support to rely upon and thus fully depends

on me for

its learning, sustenance, love and protection. I have got to admit that

it

is wrong to neglect someone who has taken shelter and must

acccordingly

act without regrets. (10) Undoubtedly all honorable and

pious souls

will, however detached they are, put aside even their most important

self-interests in order to live up to those principles as friends of

the poor.'

(7) Seeing how that deer calf being separated

from its kind, helplessly floated away in the stream, the wise king

Bharata considering it orphaned, took it as a friend compassionately to

his âs'rama. (8) Adopting

it

as

his

own

child,

feeding

it

every

day,

protecting

it,

raising

it and petting it, he got greatly

attached to this deer calf. Within a couple of days he thus, having

given up his routines, his self-restraint and his worship

of

the Original Person, lost his entire practice of detachment. (9)

'Alas! [he thought to himself], by the Controller turning the wheel of

time this creature was deprived of its family, friends and relatives.

Finding me for its shelter, it has only me as its father, mother,

brother and member of the herd. Surely having no one else it puts

great faith in me as the support to rely upon and thus fully depends

on me for

its learning, sustenance, love and protection. I have got to admit that

it

is wrong to neglect someone who has taken shelter and must

acccordingly

act without regrets. (10) Undoubtedly all honorable and

pious souls

will, however detached they are, put aside even their most important

self-interests in order to live up to those principles as friends of

the poor.'

(11) Thus having grown attached as he sat, laid down, walked, bathed, ate etc. with the young animal, his heart became captivated by affection. (12) When he went into the forest to collect flowers, firewood, kus'a grass, leaves, fruits, roots and water, he, apprehensive about wolves, dogs and other animals of prey, always took the deer with him. (13) On his way he, with a mind and heart full of love, carried it on his shoulder now and then, and kept, fond as he was of the young, it fondling it on his lap or on his chest when he slept and derived great pleasure from it. (14) During worship the emperor sometimes got up despite of not being finished, just to look after the deer calf and then felt happy bestowing all his blessings saying: 'Oh my dear calf I wish you all the best.' (15) Sometimes being separated from the calf he was so anxious that he got upset like a piteous, miserly man who has lost his riches. He then found himself in a state wherein he couldn't think of anything else anymore. Thus he ran into the greatest illusion entertaining thoughts like: (16) 'Oh, alas! My dear child, that orphan of a deer, must be very distressed. It'll turn up again and put faith in me as being a perfectly gentle member of its own kind. It will forget about me being such an ill-behaved cheater, such a bad-minded barbarian. (17) Will I see that creature protected by the gods again walk around and nibble grass unafraid in the garden of my âs'rama? (18) Or would the poor thing be devoured by one of the many packs of wolves or dogs, or else a lone wandering tiger? (19) Alas, the Supreme Lord of the entire universe, the Lord of the three Vedas who is there for the prosperity of all, is [in the form of the sun] already setting; and still this baby that the mother entrusted to me has not returned! (20) Would that princely deer of mine really return and please me who gave up his different pious exercises? It was so cute to behold. Pleasing it in a way befitting its kind drove away all unhappiness! (21) Playing with me when I with closed eyes feigned to meditate, it would angrily out of love, trembling and timidly approach to touch my body with the tips of its horns that are as soft as water drops. (22) When I grumbled at it for polluting the things placed on the kus'a grass for worship, it immediately in great fear stopped its play to sit down in complete restraint of its senses, just like the son of a saint would do. (23) Oh, what practice of penance performed by the ones most austere on this planet can bring the earth the wealth of the sweet, small, beautiful and most auspicious soft imprints of the hooves of this most unhappy creature in pain of being lost! For me they indicate the way to achieve the wealth of the body of her lands that, on all sides adorned by them, are turned into places of sacrifice to the gods and the brahmins desirous on the path to heaven! (24) Could it be that the moon [god] so very powerful and kind to the unhappy, out of compassion for the young that lost its mother in her fear for the great beast of prey, is now protecting this deer child which strayed from my protective âs'rama? (25) Or would he out of love by means of his rays, which so peaceful and cool stream from his face like nectarean water, comfort my heart, that red lotus flower to which the little deer submitted itself as my son and which now in the fire of separation burns with the flames of a forest fire?'

(26) He whose heart was saddened by a mind derived from bad karma, thus was carried away by the impossible desire of having a son that looked like a deer and consequently failed in his yoga exercises, his penances and devotional service to the Supreme Lord. How could he, attached as he was to the body of a different species, the body of a deer calf, fulfill his life's purpose now with such a hindrance... he who previously had abandoned the so difficult to forsake sons he with a loving heart had fathered? King Bharata, who, absorbed in maintaining, pleasing, protecting and fondling a baby deer, because of that obstacle was obstructed in the execution of his yoga, thus neglected [the interest of] his soul while with terribly rapid strides inevitably his time approached like a snake entering the hole of a mouse. (27) The moment he left this world he found at his side the deer lamenting like his son that had occupied his mind. With his body dying in the presence of the deer, he thereafter himself obtained the body of a deer [see also B.G. 8: 6]. [But] when he upon his death got another body, his memory of his previous existence was not destroyed. (28) In that birth as a consequence of his past devotional activities constantly remembering what the cause was of having obtained the body of a deer, he remorsefully said: (29) 'Oh what a misery! I have fallen from the way of life of the self-realized, despite of having given up my sons and home, living solitary in a sacred forest as someone who perfectly in accord with the soul takes shelter of the Supersoul of all beings and despite of constantly listening to and thinking about Him, the Supreme Lord Vâsudeva, spending all my hours with being absorbed in chanting, worshiping and remembering. In due course of time a mind fixed in such a practice turns into a mind fully established in the eternal reality, but having fallen in my affection for a young deer, I by contrast am a great fool again!'

(30) Thus in silence turning away from the world [he as] the deer gave up his deer mother and turned back from the Kâlañjara mountain where he was born, to the place where he before had worshiped the Supreme Lord, the âs'rama of Pulastya and Pulaha in the village called S'âlagrâma that is so dear to the great saints living there in complete detachment. (31) In that place eating fallen leaves and herbs, he awaited his time in the eternal company of the Supersoul and existed, vigilantly guarding against bad association, with the only motivation to put an end to the cause of his deer body that he, bathing in the water of that holy place, ultimately gave up.'

(7) Seeing how that deer calf being separated

from its kind, helplessly floated away in the stream, the wise king

Bharata considering it orphaned, took it as a friend compassionately to

his âs'rama. (8) Adopting

it

as

his

own

child,

feeding

it

every

day,

protecting

it,

raising

it and petting it, he got greatly

attached to this deer calf. Within a couple of days he thus, having

given up his routines, his self-restraint and his worship

of

the Original Person, lost his entire practice of detachment. (9)

'Alas! [he thought to himself], by the Controller turning the wheel of

time this creature was deprived of its family, friends and relatives.

Finding me for its shelter, it has only me as its father, mother,

brother and member of the herd. Surely having no one else it puts

great faith in me as the support to rely upon and thus fully depends

on me for

its learning, sustenance, love and protection. I have got to admit that

it

is wrong to neglect someone who has taken shelter and must

acccordingly

act without regrets. (10) Undoubtedly all honorable and

pious souls

will, however detached they are, put aside even their most important

self-interests in order to live up to those principles as friends of

the poor.'

(7) Seeing how that deer calf being separated

from its kind, helplessly floated away in the stream, the wise king

Bharata considering it orphaned, took it as a friend compassionately to

his âs'rama. (8) Adopting

it

as

his

own

child,

feeding

it

every

day,

protecting

it,

raising

it and petting it, he got greatly

attached to this deer calf. Within a couple of days he thus, having

given up his routines, his self-restraint and his worship

of

the Original Person, lost his entire practice of detachment. (9)

'Alas! [he thought to himself], by the Controller turning the wheel of

time this creature was deprived of its family, friends and relatives.

Finding me for its shelter, it has only me as its father, mother,

brother and member of the herd. Surely having no one else it puts

great faith in me as the support to rely upon and thus fully depends

on me for

its learning, sustenance, love and protection. I have got to admit that

it

is wrong to neglect someone who has taken shelter and must

acccordingly

act without regrets. (10) Undoubtedly all honorable and

pious souls

will, however detached they are, put aside even their most important

self-interests in order to live up to those principles as friends of

the poor.' (11) Thus having grown attached as he sat, laid down, walked, bathed, ate etc. with the young animal, his heart became captivated by affection. (12) When he went into the forest to collect flowers, firewood, kus'a grass, leaves, fruits, roots and water, he, apprehensive about wolves, dogs and other animals of prey, always took the deer with him. (13) On his way he, with a mind and heart full of love, carried it on his shoulder now and then, and kept, fond as he was of the young, it fondling it on his lap or on his chest when he slept and derived great pleasure from it. (14) During worship the emperor sometimes got up despite of not being finished, just to look after the deer calf and then felt happy bestowing all his blessings saying: 'Oh my dear calf I wish you all the best.' (15) Sometimes being separated from the calf he was so anxious that he got upset like a piteous, miserly man who has lost his riches. He then found himself in a state wherein he couldn't think of anything else anymore. Thus he ran into the greatest illusion entertaining thoughts like: (16) 'Oh, alas! My dear child, that orphan of a deer, must be very distressed. It'll turn up again and put faith in me as being a perfectly gentle member of its own kind. It will forget about me being such an ill-behaved cheater, such a bad-minded barbarian. (17) Will I see that creature protected by the gods again walk around and nibble grass unafraid in the garden of my âs'rama? (18) Or would the poor thing be devoured by one of the many packs of wolves or dogs, or else a lone wandering tiger? (19) Alas, the Supreme Lord of the entire universe, the Lord of the three Vedas who is there for the prosperity of all, is [in the form of the sun] already setting; and still this baby that the mother entrusted to me has not returned! (20) Would that princely deer of mine really return and please me who gave up his different pious exercises? It was so cute to behold. Pleasing it in a way befitting its kind drove away all unhappiness! (21) Playing with me when I with closed eyes feigned to meditate, it would angrily out of love, trembling and timidly approach to touch my body with the tips of its horns that are as soft as water drops. (22) When I grumbled at it for polluting the things placed on the kus'a grass for worship, it immediately in great fear stopped its play to sit down in complete restraint of its senses, just like the son of a saint would do. (23) Oh, what practice of penance performed by the ones most austere on this planet can bring the earth the wealth of the sweet, small, beautiful and most auspicious soft imprints of the hooves of this most unhappy creature in pain of being lost! For me they indicate the way to achieve the wealth of the body of her lands that, on all sides adorned by them, are turned into places of sacrifice to the gods and the brahmins desirous on the path to heaven! (24) Could it be that the moon [god] so very powerful and kind to the unhappy, out of compassion for the young that lost its mother in her fear for the great beast of prey, is now protecting this deer child which strayed from my protective âs'rama? (25) Or would he out of love by means of his rays, which so peaceful and cool stream from his face like nectarean water, comfort my heart, that red lotus flower to which the little deer submitted itself as my son and which now in the fire of separation burns with the flames of a forest fire?'

(26) He whose heart was saddened by a mind derived from bad karma, thus was carried away by the impossible desire of having a son that looked like a deer and consequently failed in his yoga exercises, his penances and devotional service to the Supreme Lord. How could he, attached as he was to the body of a different species, the body of a deer calf, fulfill his life's purpose now with such a hindrance... he who previously had abandoned the so difficult to forsake sons he with a loving heart had fathered? King Bharata, who, absorbed in maintaining, pleasing, protecting and fondling a baby deer, because of that obstacle was obstructed in the execution of his yoga, thus neglected [the interest of] his soul while with terribly rapid strides inevitably his time approached like a snake entering the hole of a mouse. (27) The moment he left this world he found at his side the deer lamenting like his son that had occupied his mind. With his body dying in the presence of the deer, he thereafter himself obtained the body of a deer [see also B.G. 8: 6]. [But] when he upon his death got another body, his memory of his previous existence was not destroyed. (28) In that birth as a consequence of his past devotional activities constantly remembering what the cause was of having obtained the body of a deer, he remorsefully said: (29) 'Oh what a misery! I have fallen from the way of life of the self-realized, despite of having given up my sons and home, living solitary in a sacred forest as someone who perfectly in accord with the soul takes shelter of the Supersoul of all beings and despite of constantly listening to and thinking about Him, the Supreme Lord Vâsudeva, spending all my hours with being absorbed in chanting, worshiping and remembering. In due course of time a mind fixed in such a practice turns into a mind fully established in the eternal reality, but having fallen in my affection for a young deer, I by contrast am a great fool again!'

(30) Thus in silence turning away from the world [he as] the deer gave up his deer mother and turned back from the Kâlañjara mountain where he was born, to the place where he before had worshiped the Supreme Lord, the âs'rama of Pulastya and Pulaha in the village called S'âlagrâma that is so dear to the great saints living there in complete detachment. (31) In that place eating fallen leaves and herbs, he awaited his time in the eternal company of the Supersoul and existed, vigilantly guarding against bad association, with the only motivation to put an end to the cause of his deer body that he, bathing in the water of that holy place, ultimately gave up.'